Bastiat

on why socialism cannot work

Bastiat wrote innumerable pamphlets and articles in publications.

Right up to his death, Bastiat was writing as fast as

he could, to try and make people understand the distillation

of his decades of study. Bastiat was working on Economic

Harmonies at his death.

Frédéric Bastiat on why socialism cannot work, from Economic

Harmonies, 1850.

20.90

Let us say first of all that the law must take this

stand whenever it is dealing with a debatable act or

practice, when one part of the population approves of

something of which the other part disapproves. You contend

that I am wrong to practice Catholicism; and I contend

that you are wrong to practice Lutheranism. Let us leave

it to God to judge. Why should I strike at you, or why

should you strike at me? If it is not good that one

of us should strike at the other, how can it be good

that we should delegate to a third party, who controls

the public police force, the authority to strike at

one of us in order to please the other?

20.91

You contend that I am wrong to teach my son science

and philosophy; I believe that you are wrong to teach

yours Greek and Latin. Let us both follow the dictates

of our conscience. Let us allow the law of responsibility

[consequences] to operate for our families. It will

punish the one who is wrong. Let us not call in human

law; it could well punish the one who is not wrong.

20.92

You say that I would do better to follow a given career,

to work in a given way, to use a steel plow instead

of a wooden one, to sow sparsely rather than thickly,

to buy from the East rather than from the West. I maintain

the contrary. I have made my calculations; after all,

I am more vitally concerned than you in not making a

mistake in matters that will decide my own well-being,

the happiness of my family, matters that can concern

you only as they touch your vanity or your systems.

Advise me, but do not force your opinion on me. I shall

decide at my peril and risk; that is enough, and for

the law to interfere would be tyranny.

20.93

We see, then, that in almost all of the important actions

of life we must respect men's free will, defer to their

own good judgment, to that inner light that God has

given them to use, and beyond this to let the law of

responsibility take its course.

satirical

story about candlemakers in the 19th century

on tariffs and restrictive practices

A major recurring theme in Bastiat’s

writings is his raging against the bad logic that claims

society can be enriched by taxing and preferential subsidies

for favoured client industries. Bastiat was constantly

on the alert for damaging socialist schemes that attempt

to disavantage competitors by tariffs that end up making

products more expensive for the common man. Taxes, taken

from the public and used to support unions and businesses,

inevitably undermine more productive workers and industries.

Bastiat consistently supports individual

freedom and choice, while mocking the grandiose schemes

of would-be social engineers.

In France, the manufacturers of products associated

with lighting - from candles to candlesticks, street

lamps to tapers, by way of tallow, resins, oils and

alcohol - had a brilliant idea to ensure that the domestic

market for lighting had a head start against foreign

competitors.

They would ensure that no advantage was gained from

the free light emanating from the sun, which clearly

undercuts all genuine and legitimate manufacturers of

light and lighting. This would be in line with the trade

barriers already in place against foreign suppliers

offering products such as wheat, coal, iron and textiles

at prices way lower than French producers could hope

to reach.

The National Assembly [House of Commons] was petitioned

to pass a law requiring all blinds, shutters, curtains

and other means of stopping sunlight entering into buildings

be closed - permanently.

Shutting off much access for natural light creates

a continuing demand for artificial light, thus providing

opportunities for many industries. Clearly this would

generate many positive benefits for commerce and industry,

and so society in general. The advantages would include:

- A greater demand for candles, that are made from

tallow, requiring more cattle and sheep that provide

the fat for making the tallow. Clearly, there will

be the knock-on effect of more land being cleared

and maintained for the animals, as well as increased

by-products of meat, leather, wool and manure, all

which are the basis of agricultural wealth.

- The greater demand for oil to put in oil lamps will

see the expansion in cultivation of poppies, olives

and rapeseed. Any soil depletion caused by these crops

would be offset by the increased availability of animal

manure.

- Moorland

would be covered by resinous trees, which would

draw bees to collect otherwise wasted scented pollen,

creating another industry.

- The need for more whale blubber would mean more

ship-building to increase the fleet, and so more jobs

for sailors to man the ships.

- Another industry that would grow is in the creation

and manufacture of new styles of lamps, candlesticks,

candelabras, as well as the decorating and gilding

of the items.

The whole of French industry and society would benefit

from this simple change to living conditions, from shareholders

in shipping companies to the lowliest match vendor,

thus making French industries grow considerably, and

so out-compete perfidious Albion, where manufacturing

will fail to develop as it suffers from the foolish

use of free sunlight.

[Abridged and rewritten from the original text of Economic

Sophisms, 1845]

View of the Chalossais valley from

the Place Chantilly in central Mugron

This story is a useful warning about

the inclusion of destruction and politicians’ vanity

projects in the GDP [gross domestic product] of nations,

as if such activities add to the common good without incurring

real costs.

Have you ever witnessed the anger of the good shopkeeper,

James B., when his careless son happened to break a

square of glass? If you have been present at such a

scene, you will most assuredly bear witness to the fact,

that every one of the spectators, were there even thirty

of them, by common consent apparently, offered the unfortunate

owner this invariable consolation - "It is an ill

wind that blows nobody good. Everybody must live, and

what would become of the glaziers if panes of glass

were never broken?"

Now, this form of condolence contains an entire theory,

which it will be well to show up in this simple case,

seeing that it is precisely the same as that which,

unhappily, regulates the greater part of our economical

institutions.

Suppose it cost six francs to repair the damage, and

you say that the accident brings six francs to the glazier's

trade - that it encourages that trade to the amount

of six francs - I grant it; I have not a word to say

against it; you reason justly. The glazier comes, performs

his task, receives his six francs, rubs his hands, and,

in his heart, blesses the careless child. All this is

that which is seen.

But if, on the other hand, you come to the conclusion,

as is too often the case, that it is a good thing to

break windows, that it causes money to circulate, and

that the encouragement of industry in general will be

the result of it, you will oblige me to call out, "Stop

there! your theory is confined to that which is seen;

it takes no account of that which is not seen."

It is not seen that as our shopkeeper has spent six

francs upon one thing, he cannot spend them upon another.

It is not seen that if he had not had a window to replace,

he would, perhaps, have replaced his old shoes, or added

another book to his library. In short, he would have

employed his six francs in some way, which this accident

has prevented.

Let us take a view of industry in general, as affected

by this circumstance. The window being broken, the glazier's

trade is encouraged to the amount of six francs; this

is that which is seen. If the window had not been broken,

the shoemaker's trade (or some other) would have been

encouraged to the amount of six francs; this is that

which is not seen.

And if that which is not seen is taken into consideration,

because it is a negative fact, as well as that which

is seen, because it is a positive fact, it will be understood

that neither industry in general, nor the sum total

of national labour, is affected, whether windows are

broken or not.

Now let us consider James B. himself. In the former

supposition, that of the window being broken, he spends

six francs, and has neither more nor less than he had

before, the enjoyment of a window.

In the second, where we suppose the window not to have

been broken, he would have spent six francs on shoes,

and would have had at the same time the enjoyment of

a pair of shoes and of a window.

Now, as James B. forms a part of society, we must come

to the conclusion, that, taking it altogether, and making

an estimate of its enjoyments and its labours, it has

lost the value of the broken window.

When we arrive at this unexpected conclusion: "Society

loses the value of things which are uselessly destroyed;"

and we must assent to a maxim which will make the hair

of protectionists stand on end - To break, to spoil,

to waste, is not to encourage national labour; or, more

briefly, "destruction is not profit."

What will you say, Monsieur Industriel -- what will

you say, disciples of good M. F. Chamans, who has calculated

with so much precision how much trade would gain by

the burning of Paris, from the number of houses it would

be necessary to rebuild?

I am sorry to disturb these ingenious calculations,

as far as their spirit has been introduced into our

legislation; but I beg him to begin them again, by taking

into the account that which is not seen, and placing

it alongside of that which is seen. The reader must

take care to remember that there are not two persons

only, but three concerned in the little scene which

I have submitted to his attention. One of them, James

B., represents the consumer, reduced, by an act of destruction,

to one enjoyment instead of two. Another under the title

of the glazier, shows us the producer, whose trade is

encouraged by the accident. The third is the shoemaker

(or some other tradesman), whose labour suffers proportionably

by the same cause. It is this third person who is always

kept in the shade, and who, personating that which is

not seen, is a necessary element of the problem. It

is he who shows us how absurd it is to think we see

a profit in an act of destruction. It is he who will

soon teach us that it is not less absurd to see a profit

in a restriction, which is, after all, nothing else

than a partial destruction. Therefore, if you will only

go to the root of all the arguments which are adduced

in its favour, all you will find will be the paraphrase

of this vulgar saying - What would become of the glaziers,

if nobody ever broke windows?

I was at Bordeaux. I had a cask of wine which was

worth 50 francs; I sent it to Liverpool, and the customhouse

noted on its records an export of 50 francs.

At Liverpool the wine was sold for 70 francs. My representative

converted the 70 francs into coal, which was found to

be worth 90 francs on the market at Bordeaux. The customhouse

hastened to record an import of 90 francs.

Balance of trade, or the excess of imports over exports:

40 francs.

These 40 francs, I have always believed, putting my

trust in my books, I had gained. But M. Mauguin tells

me that I have lost them, and that France has lost them

in my person.

And why does M. Mauguin see a loss here? Because he

supposes that any excess of imports over exports necessarily

implies a balance that must be paid in cash. But where

is there in the transaction that I speak of, which follows

the pattern of all profitable commercial transactions,

any balance to pay? Is it, then, so difficult to understand

that a merchant compares the prices current in different

markets and decides to trade only when he has the certainty,

or at least the probability, of seeing the exported

value return to him increased? Hence, what M. Mauguin

calls loss should be called profit.

A few days after my transaction I had the simplicity

to experience regret; I was sorry I had not waited.

In fact, the price of wine fell at Bordeaux and rose

at Liverpool; so that if I had not been so hasty, I

could have bought at 40 francs and sold at 100 francs.

I truly believed that on such a basis my profit would

have been greater. But I learn from M. Mauguin that

it is the loss that would have been more ruinous.

My second transaction had a very different result.

I had had some truffles shipped from Périgord

which cost me 100 francs; they were destined for two

distinguished English cabinet ministers for a very high

price, which I proposed to turn into pounds sterling.

Alas, I would have done better to eat them myself (I

mean the truffles, not the English pounds or the Tories).

All would not have been lost, as they were, for the

ship that carried them off sank on its departure. The

customs officer, who had noted on this occasion an export

of 100 francs, never had any re-import to enter in this

case.

Hence, M. Mauguin would say, France gained 100 francs;

for it was, in fact, by this sum that the export, thanks

to the shipwreck, exceeded the import. If the affair

had turned out otherwise, if I had received 200 or 300

francs' worth of English pounds, then the balance of

trade would have been unfavorable, and France would

have been the loser.

From the point of view of science, it is sad to think

that all the commercial transactions which end in loss

according to the businessmen concerned show a profit

according to that class of theorists who are always

declaiming against theory.

bastiat’s

regular method of reductio ad absurdum

From Frédéric

Bastiat, a man alone, pp 231-2

As Henry Hazlitt pointed out in his introduction to

one of Bastiat’s books:

He was the master of the reductio ad absurdum. Someone

suggests that the proposed new railroad from Paris

to Madrid should have a break at Bordeaux. The argument

is that if goods and passengers are forced to stop

at that city, it will be profitable for boatmen, porters,

hotelkeepers and others there. Good, says Bastiat.

But then why not break it also at Angouleme, Poitiers,

Tours, Orleans, and, in fact, at all intermediate

points? The more breaks there are, the greater the

amount paid for storage, porters, extra cartage. We

could have a railroad consisting of nothing but such

gaps-a negative railroad!

where bastiat

lived

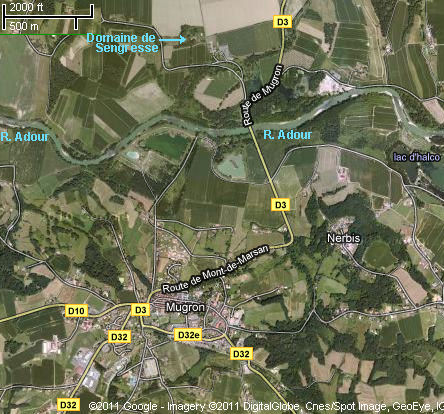

The Bastiat family property at Sengresse, near Mugron,

was acquired by Frédéric Bastiat’s

grandfather after the Revolution.

In 1825, when Bastiat was 24 years old, his grandfather

died. He inherited the manor Sengresse and over a dozen

farms. Bastiat then lived at Sengresse.

The main house and cyclamen-covered

lawn that are part of the Bastiat former estate at Sengresse,

near Mugron in Les Landes

The substantial and comfortably restored house with three

hectares (7.5 acres) now

takes paying guests.

Mugron a pretty little town, which has almost forgotten

Frédéric Bastiat, looks down over the fertile Chalossais valley. However, Bastiat is remembered in many of the

local villages and towns, which often have their own rue de Frédéric Bastiat.

There is a local organisation, le

cercle Frédéric Bastiat, that has

two missions :

- To keep alive the memory of that great humanist and

economist, Frédéric Bastiat.

- To propagate his ethics of individual liberty and

responsibility.

As well as with conferences, they fulfil their aims by

holding a dinner-debate every quarter with a disourse

and debate focussing on social and economic issues. Some

of the discourses are translated into English,

while all are available in French.

related material

citizen’s

wage

It is necessary to remember that Bastiat was financially

secure, and a land owner.

advertisement

bibliography

|

Frédéric

Bastiat, a man alone

by George Charles Roche III |

|

amazon.co.uk

Arlington House,1971

ISBN-10: 0870001167

ISBN-13: 978-0870001161

amazon.com

Arlington House, 1970

ASIN: B002TBFWUQ |

| This book is a very

useful and readable introduction to the life of Frédéric

Bastiat in the context of the history of politics

and economics. |

|

By Robert Leroux |

|

Original in French:

Lire Bastiat : Science sociale et libéralisme

Hermann, pbk, 2008

Language French

ISBN-10: 2705667156

ISBN-13: 978-2705667153

£20.01 [amazon.co.uk] {advert}

Unfortunately, the English

translation is sold at an exorbitant price. A more

reasonably priced paperback edition may appear in

due course.

Political Economy and Liberalism in France:

The Contributions of Frederic Bastiat (Routledge

Studies in the History of Economics)

Routledge, hbk,

2011

ISBN-10: 0415580552

ISBN-13: 978-0415580557

£71.25 [amazon.co.uk] {advert}

$115.56 [amazon.com] {advert} |

|

Frederic

Bastiat, Library of Economics and Liberty

Providing links to complete versions in English of

Bastiat’s main works. |

|

bastiat.net [English version]

Some

personal background to Frédéric Bastiat.. |

end notes

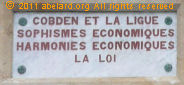

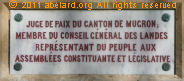

- Cobden and the League, published in 1845

Economic Sophisms, published in 1845

Economic Harmonies, published in 1850

the Law published in 1850.

- The sculptor of this statue

was Gabriel-Vital Dubray [1813-1878].

|

|